Abstract

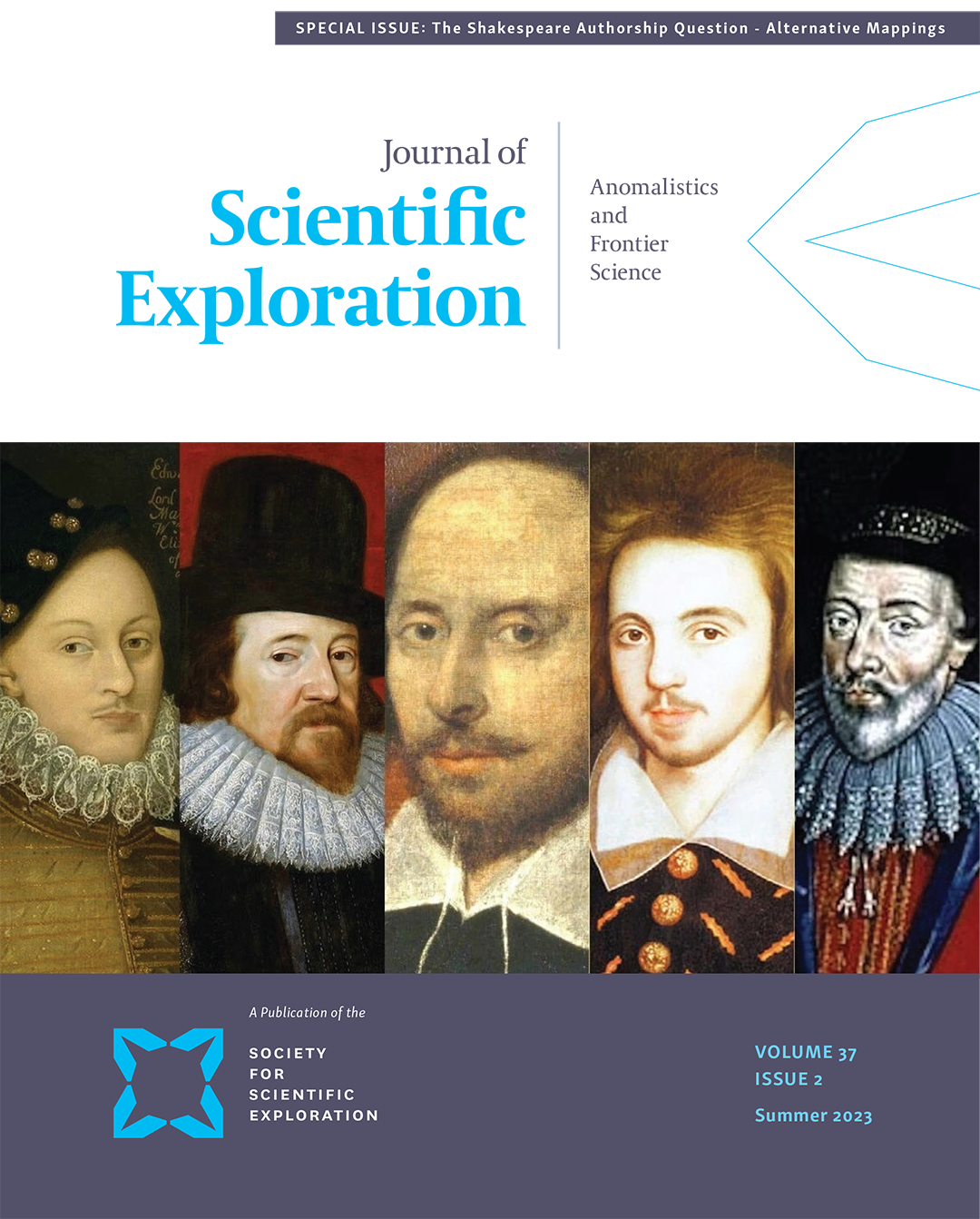

There are many ideas in the annals of science that were once ridiculed because they deviated from established “truth,” only to be rehabilitated with the passage of time. Among them: Galileo (1564-1642), punished by the Pope with house arrest for challenging the Ptolemaic theory -- a theory taught by Aristotle -- that the sun revolves around the earth; Alfred Wegener (1880-1930), who developed the theory of the movement of continental drift (later known as tectonic plates), to explain why matching prehistoric fossils could be found in places such as Europe and South America, with no known land bridges connecting them; J. Harlan Bretz (1882-1981) who showed that only cataclysmic floods could explain erosion and land formation in the Pacific Northwest, rather than the then-current theory of gradualism and “uniformitarianism.” Senior scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey in 1927 humiliated him in public; Ignaz Semelweiss (1818-1865) observed that the incidence of “childbed fever” could be significantly reduced by the use of hand disinfectant in obstetrical clinics, c. 1847. He could not provide a medical explanation beyond his observation that maternal mortality was reduced to only 1% when hand washing with disinfectant was used. He was ridiculed for going against received medical practice and committed to an asylum by colleagues after supposedly suffering a nervous breakdown. There he was beaten by guards and died from an untreated gangrenous wound. It was not until Louis Pasteur confirmed the germ theory of disease and Joseph Lister showed the benefits of surgery using hygienic methods that his life-saving observations were credited. One can add to this list the name of J. Thomas Looney (1870-1944) who began researching the question of whether the name “Shakespeare” could be a pseudonym and, if so, who the author really was. Basing his work on attributes in the plays that might match little-known poets of the Elizabethan era with the real author, he identified Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, as the man responsible in his book Shakespeare Identified published in 1920. Criticized almost immediately, his research has nevertheless stood the test of time, with more and more people worldwide now arguing for Oxford in a debate that continues unabated. This paper looks at these personal histories as well as the psychology of why “authorities” feel a need to immediately reject challenges to established positions.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2023 both author and journal hold copyright